Collaboration can bring many rewards.

Collaboration means different things to different people. Many experts describe collaboration as people working together to solve a problem or achieve a common goal. In contrast, many people in business use collaboration to refer to any meeting of minds between individuals, whether the purpose is to deliberate plans or solutions to problems, negotiate differences, administrate work assignments, and just communicate information. Collaboration used to just be called teamwork but the addition of three syllables adds more gravitas.

Communicate

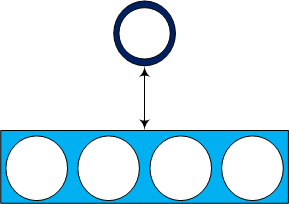

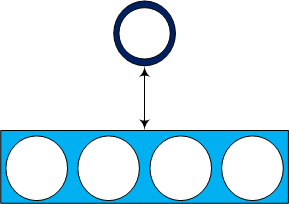

The simplest model of collaboration is one-way communication, in which information is conveyed from a leader or other knowledgeable source to other individuals. Often, this model is manifest as a supervisor relating news or other information to subordinates. Information transfer is one-way, from source to recipient, and the information is not contingent on anything the recipient does or says. Some people don’t consider communication to be collaboration, but meeting a common goal requires everyone to know the same information, so in that sense, it certainly is part of the process. Also, gossip sounds better if you call it collaboration.

Administrate

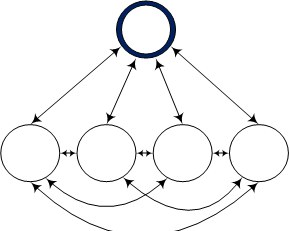

Administrative collaboration involves a two-way communication between a source and a recipient. The information the source conveys is contingent on feedback from the recipient. For example, a supervisor may assign work or give instructions on procedures to follow based on what a subordinate reports. There is no essential feedback between recipients. Some people don’t consider administration to be collaboration, but having everyone understand their role in a collaborative process is essential. When the quarterback calls a play in the huddle, you can be sure he’s hoping for a successful collaboration.

Administrative collaboration involves a two-way communication between a source and a recipient. The information the source conveys is contingent on feedback from the recipient. For example, a supervisor may assign work or give instructions on procedures to follow based on what a subordinate reports. There is no essential feedback between recipients. Some people don’t consider administration to be collaboration, but having everyone understand their role in a collaborative process is essential. When the quarterback calls a play in the huddle, you can be sure he’s hoping for a successful collaboration.

Deliberate

Deliberate

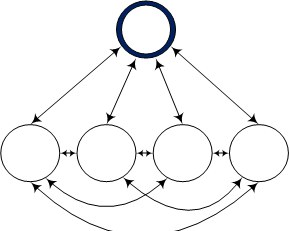

The classic model of collaboration consists of a group of individuals all communicating with each other to achieve some goal. Brainstorming is an example of this form of collaboration. Usually, there is a leader, facilitator, or at least, a recorder. Everyone deliberates together and occasionally comes upon a solution for a pressing problem, such as what to have for lunch.

Negotiate

Negotiations may involve two or more individuals, two or more groups of individuals represented by spokespersons, or some combinations of those. Interactions in negotiations are far more complex than other forms of collaboration because speakers often represent many opinions and may not even agree with what they are told to say. Sports agents and defense attorneys fall into this latter category.

Negotiations may involve two or more individuals, two or more groups of individuals represented by spokespersons, or some combinations of those. Interactions in negotiations are far more complex than other forms of collaboration because speakers often represent many opinions and may not even agree with what they are told to say. Sports agents and defense attorneys fall into this latter category.

Organization of Collaboration

Collaboration is a meeting of minds.

Business collaboration normally requires somebody to be in charge. That person might be an organizational leader, a trained facilitator, or just an informed employee who acts as the originator of the process. If you read pop business articles on collaboration, you’ll usually see a picture of a group of young, attractive, well-dressed individuals gathered around a meeting table (now called collaboration tables). The leader is the young, attractive, well-dressed individual wearing glasses, hence, having greater intelligence. Originators and informed employees are usually active contributors to collaboration; facilitators guide the process; managers take credit and assign blame. Some collaborative efforts are tightly organized to the point of being scripted and having little flexibility. Other collaboration efforts are spontaneous, having a goal but no guidelines, thus putting them one goal ahead of most business meetings.

Participants in Collaboration

Success in collaboration depends on listening to other participants.

Collaboration requires at least two participants but also can involve an unlimited number of participants. If specific individuals are invited to collaborate, such as at a meeting, the number of participants would surely be limited. That’s both an advantage and a disadvantage to meetings. Collaboration using the internet, such as through a discussion forum, can involve numerous participants. The disadvantage of forums, especially those that allow open and anonymous participation, are trolls who post ignorant and inflammatory messages. Trolls are everywhere, even in private, in-house , networking forums having no anonymity. Some people just have troll personalities.

Logistics of Collaboration

Ask most people about collaboration and they’ll describe it as a face-to-face interaction. It doesn’t have to be. In fact, there are many great examples of collaboration in which the participants were separated by space or time. Foreign diplomacy used to be, and in some cases still is, conducted this way. There’s probably no better example of collaborating at different times and locations than Kennedy and Khrushchev working out a solution to the Cuban Missile Crisis even though they were located 4,857 miles and nine time zones apart. Likewise, it is possible, and sometimes ever preferable, for collaborators to contribute their ideas at different times from different locations. This also allows greater flexibility for more interesting office misadventures.

Interaction in Collaboration

Give quiet collaborators a chance to add their thoughts.

Perhaps the first characteristic people think about when collaborating is how they will interact with others. There are several ways to communicate – by voice, text, and graphics. Vocal communication is simple but can have problems. If you’ve ever been on a conference call or virtual meeting in which speakers mumble or are drowned out by rustling papers and snoring, you know what I mean. Text can be less ambiguous if the message is honest and clearly written Text is also easier to archive than conversations, But text is a less efficient way to communicate than voice. It takes more time to plan and write a text message than it is to just babble. Likewise with graphics, you can present information more effectively but they are more laborious to prepare.

Hearing a variety of different opinions can help solve difficult problems.

Two-thirds of workers in a typical office prefer face-to-face collaboration, perhaps because they can hear voices and read facial expressions and body language. Video chat isn’t quite the same as an in-person meeting because the subtle non-verbal cues can’t be recognized on the small, sometimes pixilated, and often interrupted-motion image on a computer screen. But face-to-face communications also have disadvantages. Some people are difficult to understand because they mumble or have strong accents. Some people are intimidated or annoyed by attempts to read body language. Some people can be misleading, usually much more often by voice than by writing. Some people dominate interactions and discourage others from participating, even when the introverts outnumber the extroverts. But the greatest disadvantage of face-to-face collaboration is the prevalent belief that it is the only effective way to collaborate.

Documentation of Collaboration

It’s beneficial to have a record of what happened during a collaboration session. Meeting minutes, for example, are a common way to document the ideas that were discussed. But, meeting notes are subject to the memory, interpretation, and bias of the note taker. Some collaboration methods, on the other hand, such as email, discussion forums, and videos, not only record everything that happened but do so automatically.

Methods of Collaboration

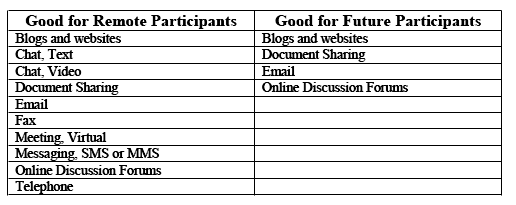

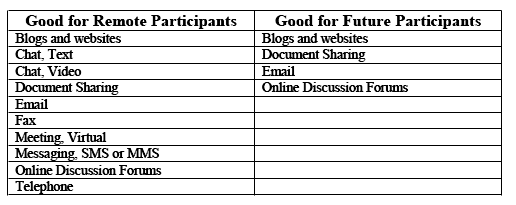

People often associate collaboration with meetings involving real time, face-to-face discussions at close quarters. There may be dozens of participants or just a few. But, there are many other ways to collaborate besides physical meetings. Telephone calls, both person-to-person and in a conference, are also tools for collaborating. There’s also the ancient but still useful fax technology. The greatest growth in methods for collaboration, however, is attributable to the Internet. Ideas can be exchanged using blogs and websites, online discussion forums, document sharing in the Cloud, virtual meetings, text and video chat, messaging, both SMS and MMS, and of course the old reliable mainstay of business communications, email.

The following table summarizes the characteristics of common methods of collaboration.

Selecting a Collaboration Model

You can accomplish any collaboration objective — communication, administration, deliberation, or negotiation — in a variety of ways. Consider your time frame. If you have a deadline for the results of your collaboration, is it close or far in to the future? Is the deadline flexible or inflexible? A flexible deadline far into the future will allow you more options for collaboration than a firm, immediate deadline.

Here’s a good place for a meeting.

Some collaboration leaders aren’t very imaginative when it comes to selecting a model for how to implement their process. The always decide to call a meeting. You’ve seen the results — meetings that are rescheduled again and again to accommodate key participants, meeting rooms that are too small for the number of participants, and meeting durations that are interminably long or too short to accomplish the goals of the collaboration.

The Internet allows you to collaborate with experts you may not even know.

In selecting a model for collaboration, a primary consideration should be the participants and their logistics. First, do you want a few specific participants or everyone who is interested in your project? That is a fundamental decision that some collaboration leaders don’t even think about. They just invite participants who are at the same level in the organization or are in their own work. It’s important to include decision makers and other stakeholders but there are usually other informed individuals available who can add to the discussions.

You also need to consider the availability of the participants, both in time and location. Sometimes the most appropriate participants for a collaboration can’t travel to attend a meeting or don’t have the time to participate. Those situations don’t have to exclude their participation. There are several methods of collaboration that work wherever the participants reside or whenever they are available to interact.

Find a way to work toward a common goal.

The objective, schedule, and participants in a collaboration should determine what methods may be appropriate. You might also consider the preferences of your participants. In a typical office, almost everyone will be able to collaborate by telephone and email. About three-quarters will be able to share documents and chat. Half will follow company blogs and websites. A third will be active in online discussion forums and messaging. Three-quarters prefer collaborating with specific individuals and half prefer same-time collaboration. Two-thirds believe their productivity depends on collaborating with their co-workers but only a quarter link their productivity to their supervisors. And perhaps not surprisingly, a quarter of workers in a typical office would prefer to work on their own rather than collaborating. Half will be introverts who might not be comfortable interacting in an open forum (no, I didn’t make this up; I have survey results).

So, select a collaboration method, or better, a combination of methods, based on the types of interaction they offer to you and your participants. Then, plan your effort. But be aware that there are a few common dilemmas in planning a collaboration effort. Here are some examples:

- Impending Deadline – You need some answers quickly. Keep the solution simple. Use the telephone, chat, or messaging.

- Participants Unavailable – You find it difficult to schedule meetings or conference calls because key participants have other obligations. Don’t wait for the perfect time or place. Schedule a virtual meeting or share documents to focus discussions for when you do meet.

- Unidentified Expertise – You know what you want to do but don’t know how to do it or who can help. This is a perfect opportunity to use a discussion forum. You won’t know when or where your answer will come, but it probably will.

- Low Priority – You want to collaborate on some issue but you’re just too busy to devote enough time to it. Share a document, write a blog, or post to a discussion forum.

- Lack of Engagement – Your meetings are dominated by certain individuals while others are reluctant to interact. Share a summary document after the meeting where the quiet participants can record their ideas

In the 1900s, few people owned or could use a telephone. Today, most teenagers carry a cell phone with them everywhere. In contrast, the fax machine entered most every office in the 1970s but is now passé. In the 1980s, few people in business had access to email. A decade later, corporate managers were still having their secretaries printing out all their emails so they could read them. Today, email has matured. Even ninety-year-old great grandmothers have multiple email addresses. In a generation, though, email may become obsolete. The point is that we can be sure that new methods of collaborating will arrive and either replace or augment older methods. To be successful, business must adapt and professional must learn new skills for collaboration.

We can haz collaboration.

Read more about using statistics at the Stats with Cats blog. Join other fans at the Stats with Cats Facebook group and the Stats with Cats Facebook page. Order Stats with Cats: The Domesticated Guide to Statistics, Models, Graphs, and Other Breeds of Data Analysis at Wheatmark, amazon.com, barnesandnoble.com, or other online booksellers.

In every data analysis, putting the analysis and the results into a comprehensible report is the final, and for some, the biggest hurdle. The goal of a technical report is to communicate information. However, the technical information is difficult to understand because it is complicated and not readily known. Add math anxiety and the all too prevalent notion that anything can be proven with statistics and you can understand why reporting on a data analysis is a challenge.

In every data analysis, putting the analysis and the results into a comprehensible report is the final, and for some, the biggest hurdle. The goal of a technical report is to communicate information. However, the technical information is difficult to understand because it is complicated and not readily known. Add math anxiety and the all too prevalent notion that anything can be proven with statistics and you can understand why reporting on a data analysis is a challenge.

Start with what you know best. In writing a data analysis report, what you know best would be the statistics, graphing, and modeling you did.

Start with what you know best. In writing a data analysis report, what you know best would be the statistics, graphing, and modeling you did. Once you understand who your audience is, you can rewrite the summary to catch the attention of your readers.

Once you understand who your audience is, you can rewrite the summary to catch the attention of your readers.