DISCLAIMER

The postings on this blog are my own (except as noted) and do not necessarily represent the positions, strategies or opinions of my current, past, and future employers, cats and other family members, relatives, social-media friends, real friends, Charlie Sheen, people who sit next to me on public transportation, or myself when I’m in my right mind.

-

Recent Posts

Archives

- October 2025

- April 2025

- July 2023

- April 2023

- February 2022

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- May 2020

- January 2019

- December 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- November 2017

- September 2017

- May 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- January 2016

- July 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- January 2014

- September 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- February 2013

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- February 2012

- May 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

RSS Links

Feedburner

-

Blogroll

Recent Posts from: Random TerraBytes

Meta

Five Things You Should Know Before Taking Statistics 101

Of the over two million college degrees that are granted in the U.S. every year, including those earned at accredited online colleges nationwide, probably two-thirds require completion of a statistics class. That’s over a million and a half students taking Statistics 101, even more when you consider that some don’t complete the course.

Everybody who has completed high school has learned some statistics. There are good reasons for that. Your class grades were averages of scores you received for tests and other efforts. Most of your classes were graded on a curve, requiring the concepts of the Normal distribution, standard deviations, and confidence limits. Your scores on standardized tests, like the SAT, were presented in percentiles. You learned about pie and bar charts, scatter plots, and maybe other ways to display data. You might even have learned about equations for lines and some elementary curves. So by the time you got to prom, you were exposed to at least enough statistics to read USA Today.

Faced with taking Statistics 101, you may be filled with excitement, ambivalence, trepidation, or just plain terror. Your instructor may intensify those feelings with his or her teaching style and class requirements. So to make things just a bit easier, here are a few concepts to remember.

Everything is Uncertain

The fundamental difference between statistics and most other types of data analysis is that in statistics, everything is uncertain. Input data have variabilities associated with them. If they don’t, they are of no interest. As a consequence, results are always expressed in terms of probabilities.

Every data measurement is variable, consisting of:

- Characteristic of Population—This is the part of a data value that you would measure if there were no variability. It’s the portion of a data value that is the same between a sample and the population the sample if from.

- Natural Variability—This part of a data value is the uncertainty or variability in population patterns. It’s the inherent differences between a sample and the population. In a completely deterministic world, there would be no natural variability.

- Sampling Variability—This is the difference between a sample and the population that is attributable to how uncharacteristic (non-representative) the sample is of the population.

- Measurement Variability—This is the difference between a sample and the population that is attributable to how data were measured or otherwise generated.

- Environmental Variability— This is the difference between a sample and the population that is attributable to extraneous factors.

The goal of most statistical procedures is to estimate the characteristic of the population, characterize the natural variability, and control and minimize the sampling, measurement, and environmental variability. Minimizing variance can be difficult because there are so many causes and because the causes are often impossible to anticipate or control. So if you’re going to conduct a statistical analysis, you’ll need to understand the three fundamentals of variance control—Reference, Replication, and Randomization.

Statistics ♥ Models

Statistics and models are closely intertwined. Models serve as both inputs and outputs of statistical analyses. Statistical analyses begin and end with models.

Statistics uses distribution models (equations) to describe what a data frequency would look like if it were a perfect representation of the population. If data follow a particular distribution model, like the Normal distribution, the model can be used as a template for the data to represent data frequencies and error rates. This is the basis of parametric statistics; you evaluate your data as if they came from a population described by the model.

Statistical techniques are also used to build models from data. Statistical analyses estimate the mathematical coefficients (parameters) for the terms (variables) in the model, and include an error term to incorporate the effects of variation. The resulting statistical model, then, provides an estimate of the measure being modeled along with the probability that the model might have occurred by chance, based on the distribution model.

Measurement Scales shape Analyses

You may not hear very much about measurement scales in Statistics 101, but you should at least be aware of the difference between nominal scales, ordinal scales, and continuous scales. Nominal scales, also called grouping or categorical scales, are like stepping stones; each value of the scale is different from other values, but neither higher nor lower. Discrete scales are like steps; each value of the scale has a distinct break from the next discrete value, which is either higher or lower. Continuous scales are like ramps; each value of the scale is just a little bit higher or lower than the next value. There are many more types of scales, especially for time scales, but that’s enough for Statistics 101.

The reason measurement scales are important is that they will help guide which graph or statistical procedure is most appropriate for an analysis. In some situations, you can’t even conduct a particular statistical procedure if the data scales are not appropriate.

Everything Starts with a Matrix

You may not realize it in Statistics 101, but all statistical procedures involve a matrix. Matrices are convenient ways to assemble data so that computers can perform mathematical calculations. If you go beyond Statistics 101, you’ll learn a lot about matrix algebra. But for Statistics 101, all you have to know is that a matrix is very much like a spreadsheet. In a spreadsheet you have rows and columns that define rectangular areas, called cells. In statistics, the rows of the spreadsheet represent individual samples, cases, records, observations, entities that you’re making measurements on, sample collection points, survey respondents, organisms, or any other point or object on which information is collected. The columns represent variables, the measurements or the conditions or the types of information you’re recording. The columns can correspond to instrument readings, survey responses, biological parameters, meteorological data, economic or business measures, or any other types of information. You usually have several sets of variables for a given set of samples. Together, the rows and the columns of the spreadsheet define the cells, which is where the data are stored. Samples (rows), variables (columns), and data (cells) are the matrix that goes into a statistical analysis. If you understand data matrices, you’ll be able to conduct statistical analyses even without your Statistics 101 instructor to help you.

Statistics is More than Description and Testing

In Statistics 101, you learn about probability, distribution models, populations, and samples. Eventually, this knowledge will enable you to be able to describe the statistical properties of a population and to test the population for differences from other populations. But these capabilities, formidable though they are, don’t reveal the truly mind boggling analyses you can do with statistics. You can:

- Describe—characterizing populations and samples using descriptive statistics, statistical intervals, correlation coefficients, and graphics.

- Compare and Test—detecting differences between statistical populations or reference values using simple hypothesis tests, and analysis of variance and covariance.

- Identify and Classify—identifying known or hypothesized entities or classifying groups of entities using descriptive statistics; statistical tests, graphics, and multivariate techniques such as cluster analysis and data mining techniques.

- Predict—predicting measurements using regression and neural networks, forecasting using time-series modeling techniques, and interpolating spatial data.

- Explain—explaining latent aspects of phenomena using regression, cluster analysis, discriminant analysis, factor analysis, and other data mining techniques.

So don’t get discouraged if you can’t see how statistics will help you in your career based on Statistics 101. There’s a lot more out there. You just have to take the first step.

Read more about using statistics at the Stats with Cats blog. Join other fans at the Stats with Cats Facebook group and the Stats with Cats Facebook page. Order Stats with Cats: The Domesticated Guide to Statistics, Models, Graphs, and Other Breeds of Data Analysis at Wheatmark, amazon.com, barnesandnoble.com, or other online booksellers.

Polls Apart

Election season is fast approaching so you can be sure a plethora of polls will soon be adding to the mayhem. Polls educate us in two ways. They tell us what we, or at least the population being polled, think. And, in a more Orwellian sense, they tell us what we should think. Polls are used to guide how the nation is governed. For example, did you know that the unemployment rate is determined from a poll, called the Current Population Survey? Polls are important, so we need to be enlightened consumers of poll results lest we come to “love Big Brother.”

Election season is fast approaching so you can be sure a plethora of polls will soon be adding to the mayhem. Polls educate us in two ways. They tell us what we, or at least the population being polled, think. And, in a more Orwellian sense, they tell us what we should think. Polls are used to guide how the nation is governed. For example, did you know that the unemployment rate is determined from a poll, called the Current Population Survey? Polls are important, so we need to be enlightened consumers of poll results lest we come to “love Big Brother.”

The growth of polling has been exponential, following the evolution of the computer and statistical software. Before 1990, the Gallup Organization was pretty much the only organization conducting presidential approval polls. Now, there are several dozen. On average, there were only one or two presidential approval polls conducted per month. Within a decade, that number had increased to more than a dozen. These pollsters don’t just ask about Presidential approval, either. Polls are conducted on every issue of real importance and most of the issues of contrived importance. Many of these polls are repeated to look for changes in opinions over time, between locations, and for different demographics. And that’s just political polls. There has been an even faster increase in polling for marketing, product development, and other business applications.

So to be an educated consumer of poll information, the first thing you have to recognize is which polls should be taken seriously. Forget internet polls. Forget polls conducted in the street by someone carrying a microphone. Forget polls conducted by politicians or special-interest groups. Forget polls not conducted by a trained pollster with a reputation to protect.

For the polls that remain, consider these four factors:

- Difference between the choices

- Margin of error

- Sampling error

- Measurement error

Here’s what to look for.

Difference between Choices

The percent difference between the choices on a survey is often the only thing people look at, with good reason. It is often the only thing that gets reported. Reputable pollsters will always report their sample size, their methods, and even their poll questions, but that doesn’t mean all the news agencies, bloggers, and other people who cite the information will do the same. But the percent difference between the choices means nothing without also knowing the margin-of-error. Remember this. For any poll question involving two choices, such as Option A versus Option B, the largest margin of error will be near a 50%–50% split. Unfortunately, that’s where the difference is most interesting, so you really need to know something about the actual margin of error.

Margin-of-Error

You might have seen surveys report that the percent difference between the choices for a question has a margin-of-error of plus-or-minus some number. In fact, the margin-of-error describes a confidence interval. If survey respondents selected Option A 60% of the time with a margin-of-error of 4%, the actual percentage in the sampled population would be 60% ± 4%, meaning between 56% and 64%, with some level of confidence, usually 95%.

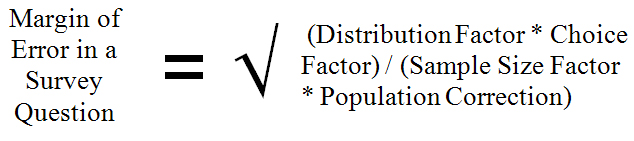

For a simple random sample from a surveyed population, the margin-of-error is equal to the square root of a Distribution Factor times a Choice Factor divided by a Sample Size Factor times a Population Correction.

- Distribution Factor is the square of the two-sided t-value based on the number of survey respondents and the desired confidence level. The greater the confidence the larger the t-value and the wider the margin-of-error.

- Choice Factor is the percentage for Option A times the percentage for Option B. That’s why the largest margin of error will always be near a 50%–50% split (e.g., 50% times 50% will always be greater than any other percentage split, like 90% times 10%).

- Sample Size Factor is the number of people surveyed. The more people you survey, the smaller the margin of error.

- Population Correction is an adjustment made to account for how much of a population is being sampled. If you sample a large percentage of the population, the margin-of-error will be smaller. The population correction ranges from 1 to about 2. It is calculated by the reciprocal of one plus the quantity the number of people surveyed (n) minus one divided by the number of people in the population (N), or in mathematical notation, 1/(1+(n-1/N)).

So the entire equation for the margin-of-error is:

Or in mathematical notation:

This formula can be simplified by making a few assumptions.

- If the population size (N) is large compared to the sample size (n), you can ignore the Population Correction. What’s large, you ask? A good rule of thumb is to use the correction if the sample size is more than 5% of the population size. If you’re conducting a census, a survey of all individuals in a population, you can’t make this assumption.

- Unless you expect a different result, you can assume the percentages for respondent choices will be about 50%–50%. This will provide the maximum estimate for the margin-of-error, ignoring other factors.

- Ignore the sample size in the Distribution Factor and use a z-score instead of a t-score. For a two-sided margin-of-error having 95% confidence, the z-score would be 1.96.

- The Distribution Factor (1.962) times the Choice Factor (50%2) equals 0.96

These assumptions reduce the equation for the margin-of-error to 1/√n. What could be simpler? Here’s a chart to illustrate the relationship between the number of responses and the margin-of-error. The margin-of-error gets smaller with an increase in the number of respondents, but the decrease in the error becomes smaller as the number of responses increases. Most pollsters don’t use more than about 1,200 responses simply because the cost of obtaining more responses isn’t worth the small reduction in the margin-of-error. Don’t worry about the Current Population Survey, though. The Bureau of Labor Statistics polls about 110,000 people every month so their margin-of-error is less than half of a percentage point.

Always look for the margin-of-error to be reported. If it’s not, look for the number of survey responses and use the chart or the equation to estimate the margin of error. Here’s a good point of reference. For 1,000 responses, the margin-of-error will be about ±3% for 95% confidence. So if a political poll indicates that your candidate is behind by two points, don’t panic; the election is still too close to call.

Sampling Error

Sampling error in a survey involves how respondents are selected. You almost never see this information reported about a survey for several reasons. First, it’s boring unless you’re really into the mechanics of surveys. Second, some pollsters consider it a trade secret that they don’t want their competition to know about especially if they’re using some innovative technique to minimize extraneous variation. Third, pollsters don’t want everyone to know exactly what they did because then it might become easy to find holes in the analysis.

Ideally, potential respondents would be selected randomly from the entire population of respondents. But you never know who all the individuals are in a population, so have to use a frame to access the individuals who are appropriate for your survey. A frame might be a telephone book, voter registration rolls, or a top-secret list purchased from companies who create lists for pollsters. Even a frame can be problematical. For instance, to survey voter preferences a list of registered voters would be better than a telephone book because not everyone is registered to vote. But even a list of registered voters would not indicate who will actually be voting on Election Day. Bad weather might keep some people at home while voter assistance drives might increase turnout of a certain demographic.

A famous example of a sampling error occurred in 1948 when pollsters conducted a telephone survey and predicted that Thomas E. Dewey would defeat Harry S. Truman. At the time, telephones were a luxury owned primarily by the wealthy, who supported Dewey. When voters, both rich and poor, went to the polls, it was Truman who was victorious. This may seem obvious in retrospect but there’s an analogous issue today. When cell phones were introduced, the numbers were not compiled into lists, so cell phone users, primarily younger individuals, were under sampled in surveys conducted over land lines.

Another issue is that survey respondents need to be selected randomly from a frame by the pollster to ensure that bias is not introduced into the study. Open-invitation internet surveys fail to meet this requirement, so you can never be sure if the survey has been biased by freepers. Likewise, if someone with a microphone approaches you on the street it’s more likely to be a late night talk show host than a legitimate pollster.

Measurement Error

Measurement error in a survey usually involves either the content of a survey or the implementation of the survey. You might get to see the survey questions but you’ll never be able to assess the validity of the way a survey is conducted.

Content involves what is asked and how the question is worded. For example, you might be asked “what is the most important issue facing our country” with the possible responses being flag burning, abortion, social security, Congressional term limits, or earmarks. Forget unemployment, the economy, wars, education, the environment, and everything else. You’re given limited choices so that other issues can be reported to be less important.

Politicians are notorious for asking poll questions in ways that will support their agenda. They also use polls not to collect information but to dissemination information about themselves or disinformation about their opponents. This is called push polling.

The last thing to think about for a poll is how the responses were collected. For autonomous surveys, look at how the questions are worded. For direct response surveys, even if you could get a copy of the script used to ask the questions, there’s no telling what was actually said, what body language was used, and so on. Professional pollsters may create the surveys but they are often implemented by minimally trained individuals.

Read more about using statistics at the Stats with Cats blog. Join other fans at the Stats with Cats Facebook group and the Stats with Cats Facebook page. Order Stats with Cats: The Domesticated Guide to Statistics, Models, Graphs, and Other Breeds of Data Analysis at Wheatmark, amazon.com, barnesandnoble.com, or other online booksellers.

Posted in Uncategorized

Tagged bias, cats, margin of error, number of samples, politics, polls, population, sample size, samples, statistics, stats with cats, surveys

4 Comments

Regression Fantasies: Part III

Is Your Regression Model Telling the Truth?

There are many technologies we use in our lives without really understanding how they work. Television. Computers. Cell phones. Microwave ovens. Cars. Even many things about the human body are not well understood. But I don’t mean how to use these mechanisms. Everyone knows how to use these things. I mean understanding them well enough to fix them when they break. Regression analysis is like that too. Only with regression analysis, sometimes you can’t even tell if there’s something wrong without consulting an expert.

Here are some tips for troubleshooting regression models.

Diagnosis

You may know how to use regression analysis, but unless you’re an expert, you may not know about some of the more subtle pitfalls you may encounter. The biggest red flag that something is amiss is the TGTBT, too good to be true. If you encounter an R-squared value above 0.9, especially unexpectedly, there’s probably something wrong. Another red flag is inconsistency. If estimates of the model’s parameters change between data sets, there’s probably something wrong. And if predictions from the model are less accurate or precise than you expected, there’s probably something wrong. Here are some guidelines for troubleshooting a model you developed.

|

Your Model |

Identification |

Correction |

| Not Enough Samples | If you have fewer than 10 observations for each independent variable you want to put in a model, you don’t have enough samples. | Collect more samples. 100 observations per variable is a good target to shoot for although more is usually better. |

| No Intercept | You’ll know it if you do it. | Put in an intercept and see if the model changes. |

| Stepwise Regression | You’ll know it if you do it. | Don’t abdicate model building decisions to software alone. |

| Outliers | Plot the dependent variable against each independent variable. If more than about 5% of the data pairs plot noticeable apart from the rest of the data points, you may have outliers. | Conduct a test on the aberrant data points to determine if they are statistical anomalies. Use diagnostic statistics like leverage to evaluate the effects of suspected outliers. Evaluate the metadata of the samples to determine if they are representative of the population being modeled. If so, retain the outlier as an influential observation (AKA leverage point). |

| Non-linear relationships | Plot the dependent variable against each independent variable. Look for nonlinear patterns in the data | Find an appropriate transformation of the independent variable. |

| Overfitting | If you have a large number of independent variables, especially if they use a variety of transformation and don’t contribute much to the accuracy and precision of the model, you may have overfit the model. | Keep the model as simple as possible. Make sure the ratio of observations to independent variables is large. Use diagnostic statistics like AIC and BIC to help select an appropriate number of variables. |

| Misspecification | Look for any variants of the dependent variable in the independent variables. Assess whether the model meets the objectives of the effort. | Remove any elements of the dependent variable from the independent variables. Remove at least one component of variables describing mixtures. Ensure the model meets the objectives of the effort with the desired accuracy and precision.. |

| Multicollinearity | Calculate correlation coefficients and plot the relationships between all the independent variables in the model. Look for high correlations. | Use diagnostic statistics like VIF to evaluate the effects of suspected multicollinearity. Remove intercorrelated independent variables from the model. |

| Heteroscedasticity | Plot the variance at each level of an ordinal-scale dependent variable or appropriate ranges of a continuous-scale dependent variable. Look for any differences in the variances of more than about five times. | Try to find an appropriate Box-Cox transformation or consider nonparametric regression or data mining methods. |

| Autocorrelation | Plot the data over time, location or the order of sample collection. Calculate a Durbin–Watson statistic for serial correlation. | If the autocorrelation is related to time, develop a correlogram and a partial correlogram. If the autocorrelation is spatial, develop a variogram. If the autocorrelation is related to the order of sample collection, examine metadata to try to identify a cause. |

| Weighting | You’ll know it if you do it. | Compare the weighted model with the corresponding unweighted model to assess the effects of weighting. Consider the validity of weighting; seek expert advice if needed. |

Sometimes the model you are skeptical about isn’t one you developed; it is models that are developed by other data analysts. The major difference is that with other analysts’ models, you won’t have access to all their diagnostic statistics and plots, let alone their data. If you have been retained to review another analyst’s work, you can always ask for the information you need. If, however, you’re reading about a model in a journal article, book, or website, you’ve probably got all the information you’re ever going to get. You have to be a statistical detective. Here are some clues you might look for.

|

Another Analyst’s Model |

Identification |

| Not Enough Samples | If the analyst reported the number of samples used, look for at least 10 observations for each independent variable in the model, |

| No Intercept | If the analyst reported the actual model (some don’t), look for a constant term. |

| Stepwise Regression | Unless another approach is reported, assume the analyst used some form of stepwise regression. |

| Outliers | Assuming the analyst did not provide plots of the dependent variable versus the independent variables, look for R-squared values that are much higher or lower than expected. |

| Non-linear relationships | Assuming the analyst did not provide plots of the dependent variable versus the independent variables, look for a lower-than- expected R-squared value from a linear model. If there are non-linear terms in the model, this is probably not an issue. |

| Overfitting | Look for a large number of independent variables in the model, especially if they different types of transformation |

| Misspecification | Look for any variants of the dependent variable in the independent variables. Assess whether the model meets the objectives of the effort. |

| Multicollinearity | Assuming relevant plots and diagnostic statistics are not available, there may not be any way to identify multicollinearity. |

| Heteroscedasticity | Assuming relevant plots and diagnostic statistics are not available, there may not be any way to identify heteroscedasticity. |

| Autocorrelation | Assuming relevant plots and diagnostic statistics are not available, there may not be any way to identify serial correlation. |

| Weighting | Compare the reported number of samples to the degrees of freedom. Any differences may be attributable to weighting. |

No Doubts

So there are some ways you can identify and evaluate eleven reasons for doubting a regression model. Remember when evaluating other analyst’s models that not everyone is an expert and that even experts make mistakes. Try to be helpful in your critiques, but at a minimum, be professional.

Read more about using statistics at the Stats with Cats blog. Join other fans at the Stats with Cats Facebook group and the Stats with Cats Facebook page. Order Stats with Cats: The Domesticated Guide to Statistics, Models, Graphs, and Other Breeds of Data Analysis at Wheatmark, amazon.com, barnesandnoble.com, or other online booksellers.

Regression Fantasies: Part II

Six More Reasons for Doubting a Regression Model

There are more than a few reasons for being skeptical about a regression model. Some are easy to identify, others are more subtle. Here are six more reasons you might doubt the validity of a regression model.

Overfitting

Overfitting involves building a statistical model solely by optimizing statistical parameters, and usually involves using a large number of variables and transformations of the variables. The resulting model may fit the data almost perfectly but will produce erroneous results when applied to another sample from the population.

The concern about overfitting may be somewhat overstated. Overfitting is like becoming too muscular from weight training. It doesn’t happen suddenly or simply. If you know what overfitting is, you’re not likely to become a victim. It’s not something that happens in a keystroke. It takes a lot of work fine tuning variables and what not. It’s also usually easy to identify overfitting in other people’s models. Simply look for a conglomeration of manual numerical adjustments, mathematical functions, and variable combinations.

Misspecification

Misspecification involves including terms in a model that make the model look great statistically even though the model is problematical. Often, misspecification involves placing the same or very similar variable on both sides of the equation.

Consider this example from economics. A model for the U.S. Gross Domestic Product (GDP) was developed using data on government spending and unemployment from 1947 to 1997. The model:

GDP = (121*Spending) – (3.5*Spending2) + (136*Time) – (61*Unemployment) – 566

had an R-squared value of 0.9994. Such a high R-squared value is a signal that something is amiss. R-squared values that high are usually only seen in models involving equipment calibration, and certainly not anything involving capricious human behavior. A closer look at the study indicated that the model term involving spending were an index of the government’s outlays relative to the economy. Usually, indexing a variable to a baseline or standard is a good thing to do. In this case, though, the spending index was the proportion of government outlays per the GDP. Thus, the model was:

GDP = (121*Outlays/GDP) – (3.5* (Outlays/GDP)2) + (136*Time) – (61*Unemployment) – 566

GDP appears on both sides of the equation, thus accounting for the near perfect correlation. This is a case in which an index, at least one involving the dependent variable, should not have been used.

Another misspecification involves creating a prediction model having independent variables that are more difficult, time consuming, or expensive to generate than the dependent variable. You might as well just measure the dependent variable when you need to know its value. Similarly with forecasting (prediction of the future) models, if you need to forecast something a year in advance, don’t use predictors that are measured less than a year in advance.

Multicollinearity

Multicollinearity occurs when a model has two or more independent variables that are highly correlated with each other. The consequences are that the model will look fine, but predictions from the model will be erratic. It’s like a football team. The players perform well together but you can’t necessarily tell how good individual players are. The team wins, yet in some situations, the cornerback or offensive tackle will get beat on most every play.

If you ever tried to use independent variables that add to a constant, you’ve seen multicollinearity in action. In the case of perfect correlations, such as these, statistical software will crash because it won’t be able to perform the matrix mathemagics of regression. Most instances of multicollinearity involve weaker correlations that allow statistical software to function, yet the predictions of the model will still be erratic.

Multicollinearity occurs often in the social sciences and other fields of study in which many variables are measured in the process of model building. Diagnosis of the problem is simple if you have access to the data. Look at correlations between the independent variables. You can also look at the variance inflation factors, reciprocals of one minus the R-squared values for the independent variables and the dependent variable. VIFs are measures of how much the model’s coefficients change because of multicollinearity. The VIF for a variable should be less than 10 and ideally near 1.

If you suspect multicollinearity, don’t worry about the model but don’t believe any of the predictions.

Heteroscedasticity

Regression, and practically all parametric statistics, requires that the variances in the model residuals be equal at every value of the dependent variable. This assumption is called equal variances, homogeneity of variances, or coolest of all, homoscedasticity. Violate the assumption and you have heteroscedasticity.

Heteroscedasticity is assessed much more commonly in analysis of variance models than in regression models. This is probably because the dependent variable in ANOVA is measured on a categorical scale while the dependent variable in regression is measured on a continuous scale. The solution to this is fairly simple. Break the dependent variable scale into intervals, like in a histogram, and calculate the variance for each interval. The variances don’t have to be precisely equal, but variances different by a factor of five are problematical. Unequal variances will wreak havoc on any tests or confidence limits calculated for model predictions.

Autocorrelation

Autocorrelation involves a variable being correlated with itself. It is the correlation between data points with the previously listed data points (termed a lag). Usually, autocorrelation involves time-series data or spatial data, but it can also involve the order in which data are collected. The terms autocorrelation and serial correlation are often used interchangeably. If the data points are collected at a constant time interval, the term autocorrelation is more typically used.

If the residuals of a model are autocorrelated, it’s a sure bet that the variances will also be unequal. That means, again, that tests or confidence limits calculated from variances should be suspect.

To check a variable or residuals from a model for autocorrelation, you can conduct a Durban-Watson test. The Durban-Watson test statistic ranges from 0 to 4. If the statistic is close to 2.0, then serial correlation is not a problem. Most statistical software will allow you to conduct this test as part of a regression analysis.

Weighting

Most software that calculates regression parameters also allows you to weight the data points. You might want to do this for several reasons. Weighting is used to make more reliable or relevant data points more important in model building. It’s also used when each data point represents more than one value. The issue with weighting is that it will change the degrees of freedom, and hence, the results of statistical tests. Usually this is OK, a necessary change to accommodate the realities of the model. However, if you ever come upon a weighted least squares regression model in which the weightings are arbitrary, perhaps done by an analyst who doesn’t understand the consequence, don’t believe the test results.

No Doubts

So, there are six more reasons for doubting a regression model. These are a bit more sophisticated than the last five reasons, and though they might appear less often, they are still good reasons for doubting a regression model. You just have to be able to diagnose and treat the regression maladies. But that is a topic for another time.

Read more about using statistics at the Stats with Cats blog. Join other fans at the Stats with Cats Facebook group and the Stats with Cats Facebook page. Order Stats with Cats: The Domesticated Guide to Statistics, Models, Graphs, and Other Breeds of Data Analysis at Wheatmark, amazon.com, barnesandnoble.com, or other online booksellers.

Posted in Uncategorized

Tagged autocorrelation, cats, dependent variable, heteroscedasticity, model, multicollinarity, overfitting, regression, variance, weighting

1 Comment

Regression Fantasies: Part I

Five Common Reasons for Doubting a Regression Model

Finding a model that fits a set of data is one of the most common goals in data analysis. Least squares regression is the most commonly used tool for achieving this goal. It’s a relatively simple concept, it’s easy to do, and there’s a lot of readily available software to do the calculations. It’s even taught in many Statistics 101 courses. Everybody uses it … and therein lies the problem. Even if there is no intention to mislead anyone, it does happen.

Here are five of the most common reasons to doubt a regression model.

Not Enough Samples

Accuracy is a critical component for evaluating a model. The coefficient of determination, also known as R-squared or R2, is the most often cited measure of accuracy. Now obviously, the more accurate a model is the better, so data analysts look large values for R-squared.

R-squared is designed to estimate the maximum relationship between the dependent and independent variables based on a set of samples (cases, observations, records, or whatever). If there aren’t enough samples compared to the number of independent variables in the model, the estimate of R-squared will be especially unstable. The effect is greatest when the R-squared value is small, the number of samples is small, and the number of independent variables is large, as shown in this figure.

The inflation in the value of R-squared can be assesses by calculating the shrunken R-square. The figure shows that for an R-squared value above 0.8 with 30 cases per variable, there isn’t much shrinkage. Lower estimates of R-square, however, experience considerable shrinkage.

You can’t control the magnitude of the relationship between a dependent variable and a set of independent variables, and often, you won’t have total control over the number of samples and variables either. So, you have to be aware that R-squared will be overestimated and treat your regression models with some skepticism.

No Intercept

Almost all software that performs regression analysis provides an option to not include an intercept term in the model. This sounds convenient, especially for relationships that presume a one-to-one relationship between the dependent and independent variables. But when an intercept is excluded from the model, it’s not omitted from the analysis; it is set to zero. Look at any regression model with “no intercept” and you’ll see that the regression line goes through the origin of the axes.

With the regression line nailed down on one end at the origin, you might expect that the value of R-squared would be diminished because the line wouldn’t necessarily travel through the data in a way that minimizes the differences between the data points and the regression line, called the errors or residuals. Instead, R-squared is artificially inflated because when the correction provided by the intercept is removed, the total variation in the model increases. But, the ratio of the variability attributable to the model compared to the total variability also increases, hence the increase in R-squared.

The solution is simple. Always have an intercept term in the model unless there is a compelling theoretical reason not to include it. In that case, don’t put all your trust in R-square (or the F-tests).

Stepwise Regression

Stepwise regression is a data analyst’s dream. Throw all the variables into a hopper, grab a cup of coffee, and the silicon chips will tell you which variables yield the best model. That irritates hard-core statisticians who don’t like amateurs messing around with their numbers. You can bet, though, that at least some of them go home at night, throw all the food in their cupboard into a crock pot, and expect to get a meal out of it.

The cause of some statistician’s consternation is that stepwise regression will select the variables that are best for the dataset, but not necessarily the population. Model test probabilities are optimistic because they don’t account for the stepwise procedure’s ability to capitalize on chance. Moreover, adding new variables will always increase R-squared, so you have to have some good ways to decide how many variables is too many. There are ways to do this. So using stepwise regression alone isn’t a fatal flow. Like with guns, drugs, and fast food, you have to be careful how you use it.

If you use stepwise regression, be sure to look at the diagnostic statistics for the model. Also, verify your results using a different data set by splitting the data set before you do any analysis, by randomly extracting observations from the original data set to create new data sets, or by collecting new samples.

Outliers

Outliers are a special irritant for data analysts. They’re not really that tough to identify but they cause a variety of problems that data analysts have to deal with. The first problem is convincing reviewers not familiar with the data that the outliers are in fact outliers. Second, the data analysts have to convince all reviewers that what they want to do with them, delete or include or whatever, is the appropriate thing to do. One way or another, though, outliers will wreak havoc with R-squared.

Consider this figure, which comes from an analysis of slug tests to estimate the hydraulic conductivity of an aquifer. The red circles show the relationship between rising-head and falling-head slug tests performed on groundwater monitoring wells. The model for this relationship has an R-square of 0.90. The blue diamond is an outlier along the trend (same regression equation) about 60% greater than the next highest value. The R-squared of this equation is 0.95. The green square is an outlier perpendicular to the trend. The R-squared of this equation is 0.42. Those are fairly sizable differences to have been caused by a single data point.

How should you deal with outliers? I usually delete them because I’m usually looking to model trends and other patterns. But outliers are great thought provokers. Sometimes they tell you things the patterns don’t. If you’re not comfortable deciding what to do with an outlier, run the analysis both with and without outliers, a time consuming and expensive approach. The other approach would be to get the reviewer, an interested stakeholder, or an independent expert involved in the decision. That approach is time consuming and expensive too. Pick your poison.

How should you deal with outliers? I usually delete them because I’m usually looking to model trends and other patterns. But outliers are great thought provokers. Sometimes they tell you things the patterns don’t. If you’re not comfortable deciding what to do with an outlier, run the analysis both with and without outliers, a time consuming and expensive approach. The other approach would be to get the reviewer, an interested stakeholder, or an independent expert involved in the decision. That approach is time consuming and expensive too. Pick your poison.

Non-linear relationships

Linear regression assumes that the relationship between a dependent variable and a set of independent variables are additive, or linear. If the relationship is actually nonlinear, the R-squared for the linear model will be lower than it would be for a better fitting nonlinear model.

This figure shows the relationship between the number of employed individuals and the number of individuals not in the U.S. work force between 1980 and 2009. The linear model has a respectable R-squared value of 0.84, but the polynomial model fits the data much better with an R-squared value of 0.95.

Non-linear relationships are a relatively simple problem to fix, or at least acknowledge, once you know what to look for. Graph your data and go from there.

Non-linear relationships are a relatively simple problem to fix, or at least acknowledge, once you know what to look for. Graph your data and go from there.

No Doubts

So there are five of the most common reasons for doubting a regression model. If you’re grasping for flaws in a regression model, these are the best places to start looking. They occur commonly and are simple to identify. But, there are plenty more reasons to question a regression model, such as multicollinearity, weighting, overfitting, and misspecification. But those are topics for another time.

Read more about using statistics at the Stats with Cats blog. Join other fans at the Stats with Cats Facebook group and the Stats with Cats Facebook page. Order Stats with Cats: The Domesticated Guide to Statistics, Models, Graphs, and Other Breeds of Data Analysis at Wheatmark, amazon.com, barnesandnoble.com, or other online booksellers.

Aphorisms for Data Analysts

An aphorism is a pithy saying that reveals some astute observation or popular notion, whether true or fictitious. “Lies, damn lies, and statistics” you’ve undoubtedly heard. If you’ve taken Stats 101, you probably know that “correlation doesn’t imply causation.” Here are a few more for your consideration.

- No data analyst is an island. Be sure you have the resources you need to complete an analysis. Get help if you need it, but never pass up the opportunity to learn new things.

- Quality begins with staffing. Support those who generate your data. Pick good people. Give them clear, well written procedures. Train them. Provide positive feedback. And thank them when they’re done.

- Start at the beginning. Plan your work. Work your plan. Expect the unexpected. Ask the right questions. Beware of preconceived notions. Fairly consider alternatives. Sometimes you get lucky, just don’t count on it.

- Applied statistics is about compromise. The way an analysis gets done often depends as much on the administrative details as the technical details. “Stay within budget.” “Finish on time.” “Don’t collect any more samples.” “Don’t tell anyone what you’re doing.” Most mind-bending, though, is that every stakeholder will have different agendas but you won’t always be able to tell what they are. Be patient and don’t lose sight of your goal.

- Statistics need a good foundation. You’ll never find the answer if you don’t measure the right things on the right subjects.

- Precision trumps accuracy. You can’t understand the data without controlling variance. You can’t control variance without understanding the data. Variance doesn’t go away just because you ignore it.

- Know your data. The more you know about your data the better your analysis will be. Understanding the big picture leads to better answers but failure lurks in the details.

- Samples are like potato chips. You can never have just one. You always want more than you have. And by the time you think you’ve had enough, you’ve had way too many.

- More data are better but better data are best. Garbage in; garbage out. Get the right data and get the data right before you start the analysis. Conducting a sophisticated analysis of poor data is like painting rotted wood. It won’t hold up to even a cursory inspection.

- Statistics don’t replace common sense. Don’t sacrifice good sense for convenience. You can’t turn off your meat computer just because you have a few silicon chips at your disposal.

- Have many tools; use the best one. There is usually more than one way to analyze a dataset. Use the best tool you have or get a new one that’s appropriate. A mechanic who only uses a wrench isn’t a very good mechanic.

- Know when to fish and when to cut bait. If at first you don’t succeed, try and try again, just don’t be compulsive about it. Knowing when to quit is usually spelled out in your budget and schedule. It’s OK if the analysis raises more questions than it answers. That’s part of knowledge discovery.

- There’s a reason analysis begins with anal. Always evaluate the validity of your assumptions, your data scrubbing, and your interpretations. If you don’t, someone else will.

- Statistics are rarely black-and-white. Correlation doesn’t necessarily imply causation. Statistical significance doesn’t necessarily imply meaningfulness. Accuracy doesn’t necessarily imply precision. Be sure you understand what the numbers are really saying.

- No result is better than the way it is presented. Even the right answer doesn’t stand alone. An analysis is only as successful as the use to which it is put.

- You can’t always get what you want. When you don’t get the answers you and your client want, remember that there are more things to consider than just the numbers. Even a flawed study can yield valuable results.

- Archive your work. You never understand the important of an analysis you conduct until much later. It may be a method you used, problems you overcame, results you found, or text you wrote. Save your work in more than one way. Storage formats come and go.

You can find more aphorisms at Aphorisms Galore.

Read more about using statistics at the Stats with Cats blog. Join other fans at the Stats with Cats Facebook group and the Stats with Cats Facebook page. Order Stats with Cats: The Domesticated Guide to Statistics, Models, Graphs, and Other Breeds of Data Analysis at Wheatmark, amazon.com, barnesandnoble.com, or other online booksellers.

Posted in Uncategorized

Tagged accuracy, cats, client, correlation coefficient, data scrubbing, information, objectives, precision, samples, statistical analysis, statistics, stats with cats, variability, variance

1 Comment

Getting the Right Answer

The academic world of statistics stresses understanding theory, types of analyses, calculations and interpretations. In the world of profit-driven business and government regulations, though, there’s even more to consider, especially if you are conducting the analysis for a boss or other client. How you propose to do the work, how you support the data generation, how you interact with others, how you package the results, and what you recommend your client should do are all part of the big picture. Here is an opportunity to practice skills that a statistician needs to have in addition to the number crunching.

Jamais Vu?

If you’ve completed Stats 101, it’s not unlikely that, one day, your boss will ask you to analyze some data. You may be assigned that job because you are the only person in the office who has the training. You may be assigned the job because you are smart, curious, and have the ability to quickly learn new skills on your own. You may be assigned the job because you are a rising star who the boss wants to give an opportunity to shine. Or, you may just be the most junior staff member in the office, and so, are the dumping grounds for all the crap assignments.

Here are six hypothetical situations for you to practice on. These scenarios are brief descriptions, devoid of many essential facts yet chocked with superfluous distractions. Feel free to customize the scenarios to stimulate your own thinking and any discussions you may have with other data analysts.

There are no unique correct answers. A student will answer differently from a seasoned professional. A data analyst trained in mathematics will answer differently from an individual trained in economics or engineering. What’s important is that you visualize how you might go about approaching these scenarios. And so …

- You are Chris, a new hire at a small nonprofit organization dedicated to consumer-protection. The city’s public transit system is in the process of requesting funding from the State for the purchase of new busses and train cars to replace obsolete equipment. The new equipment is needed desperately because many of the vehicles are well past their design life and can be repaired only by hand fabricating replacement parts. The system is touting improvements in its traditionally poor on-time performance and customer satisfaction since the new CEO, Fred, took over two years ago. They cite this as evidence that the system merits an infusion of cash to continue its equipment replacement program. There have been dozens of rallies held to support the system, including a sit-in in the mayor’s office, which was covered by the local TV news consumer reporter, Ned. One counter-protest was also held to oppose a rumored expansion of the maintenance yard in a minority community, but this did not make the news. The District’s Representative to the State Legislature, Ted, has championed the transit system’s cause by writing the funding legislation. Ted also promised to lobby Jed, one of the State’s two U.S. Senators, for a Federal grant to expand the system. A political opponent of Jed’s accused him of taking kickbacks, but no charges were ever filed. Fred and Ted are fraternal twins. Fred is a redhead like his mother, Ingrid. Ted is bald like his father, Jed. Your organization has obtained public records for the past five years on the system’s riders, customer satisfaction, and on-time performance. The information includes for each route the number of riders on each conveyance (bus or train), the number of seats available on the conveyance, the actual and scheduled times for the run, and any comments on equipment malfunctions or EMT/police calls for assistance. There are five train routes run twenty times per day and one hundred bus routes run fifty times a day. Because you took Stats 101, your boss, Ingrid, has asked you to analyze the data to see if the transit system’s claims are valid. You’re anxious to impress everyone on your first assignment. What would you do?

- You are Dawn. You made a bet with your friend Bob that your favorite weather forecaster, Ororo Munroe, is more accurate than his favorite forecaster, David Drake. You want to design a study that you and Bob can carry out to determine who the better weather person is. What would you do?

- You are Darren, a college student in a Quantitative Methods class. Your semester assignment is to conduct a survey of students involving some aspect of campus life. You plan to major in psychology so you need to make sure the survey project is done well. Because you arrived late for class, you ended up in the last group consisting of a jock, a nerd, a miscreant, a snob, and a stoner. You volunteer to be leader of the group. The group decides to study preferences in coffee consumption by comparing the preferences of students for different sizes and types of coffee drinks from two local coffee shops. You also want to analyze characteristics of the students, perhaps attributes like sex, age, race, class year, and height/weight. The nerd also wants to analyze the chemistry of the coffee drinks using variables such as water hardness and iron content, coffee bean type, sugar content, and temperature. The jock wants to conduct the survey in the fraternities and sororities on campus because he has contacts in all the houses who will facilitate the study. The snob, on the other hand, wants to conduct the survey anonymously over the web instead of in person because it will be less work. The miscreant wants to get free food and drinks from the coffee shops and later, sell them the data and results. The stoner also wants to gather data on drug usage and frequency and type of sexual activity to compare to the coffee preferences. You have ten weeks to complete the project. What would you do?

- You are Lois, an average resident of an average middle-class community in an average city of about 50,000. Over the past two years, you’ve heard from at least a dozen neighbors about someone in their families being diagnosed with a rare form of brain cancer. You asked State health officials to investigate the occurrences but they dismissed your concerns as coincidental. What would you do?

- You are Sid, a math teacher in a large urban high school of about 2,500 students. As a fifth-year teacher, you will receive tenure at the end of the year if you receive another year of satisfactory ratings. Your last review contained a recommendation that you become more involved in supporting the school’s administration. Principal Onyx, your boss, is especially concerned about security because of the growing number of incidences of in-school violence occurring across the country. He has compiled hundreds of reports on current and former students who have had illegal and otherwise prohibited items confiscated, ranging from weapons and drugs to cell phones and gum. Each report has information on the student’s background, including grades, family address and contact information, medical information, and a log of disciplinary actions. Onyx indicated that he will also provide similar files on students who have had no disciplinary actions, which can be used for comparison. If needed, he said he has a contact in the Sheriff’s office who can obtain information on student vehicles and traffic violations. The Principal wants you to develop a model to predict which students would be most likely to have contraband or be involved in some infraction of school rules. What would you do?

- You are Liz. For the past four years you have sold your artwork through an Internet web site a friend built for you. Now, you’re thinking of quitting your day job and selling your art full time. It’s a big decision with a lot of uncertainty and risk, so you decide to look at the data accumulated by the website database. The data includes: number of visitors, their Internet location, the pages viewed on your site, and the sites they visited before and after your site. For customers who purchased artwork, you also have data on: type of art, product price, tax, shipping, customer delivery address, credit card information, and gift wrap options. You looking for the data to give you profiles of your website visitors and customers, and from that, tell you how to improve your sales. If you can generate enough sales, you can fulfill your life’s dream of making a living from your artwork. What would do you do?

Did You Consider …

Here are some things to think about as you go through the hypothetical situations:

- What is the problem or question that needs to be addressed by the analysis? How important would the analysis be? Should the work even be done? Is there a better way to answer the question or solve the problem than statistics?

- Who would do the work, you or some hired help? If you would hire a data analyst to do the work, how would you identify, contract, manage, and compensate him or her? If you plan to do the work yourself, how can you leverage your primary area of expertise to the problem? What help, (e.g., people, information, tools) might you need to obtain?

- Are there valid data available or would they have to be generated? If you need to generate data, how will you control bias and variability? Could publicly available information be used to augment the data?

- What data analysis techniques would need to be used? What software and special expertise would you need? Are there technical assumptions or caveats that should be considered?

- Could the analysis be kept small (e.g., relatively unsophisticated descriptive statistics and graphs), completed in steps (e.g., initially at a small scale like a pilot study), or would the study need to be thorough and technically defensible?

- How long do you think it will take to scrub and analyze the data? Where might the schedule for getting the work done be problematical? Would funding be needed, and if so, where might it come from? Might the source of funding introduce any unintentional bias or apparent conflict-of-interest?

- Is there likely to be media attention or legal proceedings associated with the results? Are there any potential ethical dilemmas or political complications? Are you competing with someone else for the work? Might the results produce some undesirable outcome? What other risks to you, your client, and other stakeholders might there be in the work?

Oh, and don’t forget all the statistical specifications and decisions you have to address.

Getting the Answer that’s Right for You

In life, the correct answers aren’t in the back of the book. Sometimes, there are more than one, even many acceptable answers. Sometimes there are none. Analyzing data is like taking a long road trip. Most of the trip has nothing to do with your destination but you have to go through it to get there. If you’re not proficient in data analysis, it can be like the last bridge, tunnel, or traffic jam you have to get by, white-knuckled and sweating, before you reach your destination. If you are a statistician, it’s more like the last rest stop where you can relieve your pent up anxiety before you cruise home. Whether your analysis will be an aggravating traffic jam or a tranquil rest stop will depend on your confidence. Confidence comes from practice. Go for it!

Read more about using statistics at the Stats with Cats blog. Join other fans at the Stats with Cats Facebook group and the Stats with Cats Facebook page. Order Stats with Cats: The Domesticated Guide to Statistics, Models, Graphs, and Other Breeds of Data Analysis at Wheatmark, amazon.com, barnesandnoble.com, or other online booksellers.

Posted in Uncategorized

Tagged cats, ethics, examples, homework, problems, statistical analysis, stats with cats

1 Comment

Ten Tactics used in the War on Error

Scientists and other theory-driven data analysts focus on eliminating bias and maximizing accuracy so they can find trends and patterns in their data. That’s necessary for any type of data analysis. For statisticians, though, the real enemy in the battle to discover knowledge isn’t so much accuracy as it is precision. Call it lack of precision, variability, uncertainty, dispersion, scatter, spread, noise, or error, it’s all the same adversary.

One caution before advancing further. There’s a subtle difference between data mining and data dredging. Data mining is the process of fining patterns in large data sets using computer algorithms, statistics, and just about anything else you can think of short of voodoo. Data dredging involves substantial voodoo, usually involving overfitting models to small data sets that aren’t really as representative of a population as you might think. Overfitting doesn’t occur in a blitzkrieg; it’s more of a siege process. It takes a lot of work. Even so, it’s easy to lose track of where you are and what you’re doing when you’re focused exclusively on a goal. The upshot of all this is that you may be creating false intelligence. Take the high ground. Don’t interpret statistical tests and probabilities too rigidly. Don’t trust diagnostic statistics with your professional life. Any statistician with a blood alcohol level under 0.2 will make you look silly.

Here are ten tactics you can use to try to control and reduce variability in a statistical analysis.

Know Your Enemy

There’s an old saying, six months collecting data will save you a week in the library. Be smart about your data. Figure out where the variability might be hiding before you launch an attack. Focus at first on three types of variability—sampling, measurement, and environmental.

Sampling variability consists of the differences between a sample and the population that are attributable to how uncharacteristic (non-representative) the sample is of the population. Measurement variability consists of the differences between a sample and the population that are attributable to how data were measured or otherwise generated. Environmental Variability consists of the differences between a sample and the population that is attributable to extraneous factors. So there are three places to hunt for errors—how you select the samples, how you measure their attributes, and everything else you do. OK, I didn’t say it was going to be easy.

Start with Diplomacy

Start by figuring out what you can do to tame the error before things get messy. Consider how you can use the concepts of reference, replication, and randomization. The concept behind using a reference in data generation is that there is some ideal, background, baseline, norm, benchmark, or at least, generally accepted standard that can be compared to all similar data operations or results. If you can’t take advantage of a reference point to help control variability, try repeating some aspects of the study as a form of internal reference. When all else fails, randomize.

Five maneuvers you can try in order to control, minimize, or at least be able to assess the effects of extraneous variability,are :

- Procedural Controls—like standard instructions, training, and checklists.

- Quality Samples and Measurements—like replicate measurements, placebos, and blanks.

- Sampling Controls—like random, stratified, and systematic sampling patterns.

- Experimental Controls—randomly assigning individuals or objects to groups for testing, control groups, and blinding.

- Statistical Controls—Special statistics and procedures like partial correlations and covariates.

Even if none of these things work, at least everybody will know you tried.

Prepare, Provision, and Deploy

Before entering the fray, you’ll want to know that your troops data are ready to go. You have to ask yourself two questions—do you have the right data and do you have the data right? Getting the right data involves deciding what to do about replicates, missing data, censored data, and outliers. Getting the data right involves making sure all the values were generated appropriately and the values in the dataset are identical to the values that were originally generated. Sorting, reformatting, writing test formulas, calculating descriptive statistics, and graphing are some of the data scrubbing maneuvers that will help to eliminate extraneous errors. Once you’ve done all that, the only thing left to do is lock and load.

Perform Reconnaissance

While analyzing your data, be sure to look at errors in every way you can. Is it relatively small? Is it constant for all values of the dependent variable? Infiltrate the front line of diagnostic statistics. Look beyond r-squares and test probabilities to the standard error of estimate, DFBETAs, deleted residuals, leverage, and other measures of data influence. What you learn from these diagnostics will lead you through the next actions.

Divide and Conquer

Perhaps the best, or at least the most common, way to isolate errors is to divide the data into more homogeneous groups. There are at least three ways you can do this. First, and easiest, is to use any natural grouping data you might have in your dataset, like species or sex. There may also be information you can use to group the data in the metadata. Second is the more problematical visual classification. You may be able to classify your data manually by sorting, filtering, and most of all, plotting. For example, by plotting histograms you may be able to identify thresholds for categorizing continuous-scale data into groups, like converting weight into weight classes. Then you can analyze each more homogeneous class separately. Sometimes it helps and sometimes it’s just a lot of work for little result. The other potential problems with visual classification are that it takes a bit of practice to know what to do and what to look for, and more importantly, you have to be careful that your grouping isn’t just coincidental.

The third method of classifying data is the best or the worst, depending on your perspective. Cluster analysis is unarguably the best way to find the optimal groupings in data. The downside is that the technique requires even more skill and experience than visual classification, and furthermore, the right software.

Call in Reinforcements

If you find that you need more than just groupings to minimize extraneous error, bring in some transformations. You can use transformations to rescale, smooth, shift, standardize, combine, and linearize data, and in the process, minimize unaccounted for errors. There’s no shame in asking for help—not physical, not mental, and not mathematical.

Shock and Awe

If all else fails, you can call in the big guns. In a sense, this tactic involves rewriting the rules of engagement. Rather than attacking the subjects, you aim at reducing the chaos in the variables. The main technique to try is factor analysis. Factor analysis involves rearranging the information in the variables so that you have a smaller number of new variables (called factors, components or dimensions, depending on the type of analysis) that represent about the same amount of information. These new factors may be able to account for errors more efficiently than the original variables. The downside is that the factors often represent latent, unmeasurable characteristics of the samples, making them hard to interpret. You also have to be sure you have appropriate weapons of math production (i.e., software) if you’re going to try this tactic.

Set Terms of Surrender

If you’re been pretty aggressive in torturing your data, make sure the error enemy is subdued before declaring victory. Errors are like zombies. Just when you think you have everything under control they come back to bite you. Rule 2: Always double tap. In statistics, this means that you have to verify your results using a different data set. It’s called cross validation and there are many approaches. You can split the data set before you do any analysis, analyze one part (the training data set), and then verify the results with the other part (the test data set). You can randomly extract observations from the original data set to create new datasets for analysis and testing. Finally, you can collect new samples. You just want to be sure no errors are hiding where you don’t suspect them

Have an Exit Strategy

In the heat of data analysis, sometimes it’s difficult to recognize when to disengage. Even analysts new to the data can fall into the same traps as their predecessors. There are two fail-safe methods for knowing when to concede. One is to decide if you have met the specific objective that you defined before you mobilized. If you did, you’re done. The other is to monitor the schedule and budget your client gave you to solve their problem. When you get close to the end, it’s time to withdraw. Be sure to save some time and money for the debriefing.

Live to Fight another Day

You don’t have to surrender in the war against error. In fact, every engagement can bring you closer to victory. If an analysis becomes intractable, follow the example of Dunkirk. Withdraw your forces, call your previous efforts a pilot study, and plan your next error raid.

Read more about using statistics at the Stats with Cats blog. Join other fans at the Stats with Cats Facebook group and the Stats with Cats Facebook page. Order Stats with Cats: The Domesticated Guide to Statistics, Models, Graphs, and Other Breeds of Data Analysis at Wheatmark, amazon.com, barnesandnoble.com, or other online booksellers.

It’s All Relative

It’s easy to quote someone out of context to impart a false impression. A movie critic might write a review saying, “This film is a delight compared to a colonoscopy” only to be quoted as saying, “This film is a delight.” Likewise, data presented without context may be misleading if they are related to other factors important to an analysis.

In analyzing data, some quantities are absolute in the sense that they mean the same thing under most conditions while others are relative to other influencing factors. Take a person’s age. If you are analyzing healthy six-year-old subjects, you would expect certain characteristics and behaviors that might vary within some typical range, but would be quite different from, say, sixty-year-old subjects. However, if your six-year-old subjects came from different cultures and geographies, you might find that their characteristics and behaviors are substantially different. In some societies, six-year-olds are protected innocents while in others they are hunters-in-training.

The Incredible Shrinking Government

Consider this example. How many times have you heard political pundits rant about the unbridled growth of the U.S. federal government? Is that really true? Sure, the government spends more dollars and has more employees than fifty years ago. But that’s to be expected because the country’s economy and population are both growing. It’s like a family that pays more for groceries to feed their hungry teenagers than they did when they were young children. So the government is indeed growing along with the rest of the country, but like children fueling an increase in grocery expenditures, the growth of the government is fueled by the growth of the economy and the population. If you want to examine the growth of the federal government, you have to compensate for the growth of the economy and the population. That’s what this chart does using data from a variety of federal websites.

Between 1960 and today, annual federal expenditures have been a fairly constant 20% of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP). The percentage was a bit less in the 1960s and 1970s, and a bit more in the 1980s. There have been two blips in the otherwise flat data trend—one in 1976 when the government changed its fiscal year, and one in 2009 attributable to the Troubled Asset Relief Program of 2008 (TARP, the Bailout) and the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (ARRA, the Stimulus). Overall, though, the amount the government spends is growing at about the same rate as the economy.

Between 1960 and today, annual federal expenditures have been a fairly constant 20% of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP). The percentage was a bit less in the 1960s and 1970s, and a bit more in the 1980s. There have been two blips in the otherwise flat data trend—one in 1976 when the government changed its fiscal year, and one in 2009 attributable to the Troubled Asset Relief Program of 2008 (TARP, the Bailout) and the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (ARRA, the Stimulus). Overall, though, the amount the government spends is growing at about the same rate as the economy.

What about the federal workforce? The U.S. government is the largest employer in the world and it’s growing, but again, the growth is in response to the country’s growth in population. In fact, the chart shows that the number of full-time equivalent positions (FTEs) per thousand of population has decreased from 11 in 1960 to about 6 in 2009. The jump of half a percentage point in 2010 is attributable to the people the government hired for the 2010 Census, and more importantly, the people hired to administer TARP and ARRA. This data is for the Executive Branch of the government only and does not include Post Office Employees. The Office of Management and Budget has estimated that with Post Office FTEs, the ratio was 13.3 in 1962 and about 8.4 in 2010, but the trend is still downward.

Another popular rant of the political pundits is that Democrats grow the government and Republicans shrink the government. In the chart, the red lines represent Republican control of the government and the blue lines represent Democratic control of the government. Democrats have controlled the Presidency and both Houses of Congress five times in the past fifty years. The number of federal employees per the country’s population decreased substantially under Clinton, decreased slightly under Kennedy and Carter, remained about the same under Johnson, and increased under Obama. Republicans have controlled the Presidency and both Houses of Congress only once since 1960. The number of federal employees per the population remained about the same under G. W. Bush. So, it doesn’t matter who is in office, the government grows in line with the growth of the economy and the population. Don’t let those political pundits tell you differently.

Around the World in FTE Haze

Here’s another example along the same lines using data from http://www.numberof.net/number-of-government-employees-in-the-world/ and http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_countries_by_population.

This table shows that the U.S. has a relatively large number of federal employees for its population and would top the list if the USPS employees were included. About a third of the countries have one government employee or less per 1,000 population. China with its huge population has the lowest ratio. The U.S. government may be getting smaller but it’s still way bigger than any other government in the world. Right? Maybe, but before you go all libertarian, consider this.